Linux Corporate Infrastructure

The biggest Linux success story is one too few IT workers can tell.

At the O'Reilly Open Source Convention (OSCon) last summer, the killer talk wasn't one of the keynotes, although most of those were excellent. It was a breakout session called "Commercial OSS Business". The panel featured an A-list lineup: Matt Asay, Director of Novell's Linux Business Office and founder of the Open Source Business Conference; Brian Behlendorf, founder of the Apache Foundation and CollabNet; Bob Lisbonne, a VC with Matrix Partners; Jason Matusow, Director of Microsoft's Shared Source Initiative; and Zack Urlocker, Marketing VP with MySQL. The moderator was Tim O'Reilly himself.

They all had terrific stuff to say, much of it quotable. Yet the best contributor to the session wasn't a panelist at all, but an audience member who grabbed the microphone, stood in front of the stage and put on a performance worthy of Frank Sinatra fronting the Tommy Dorsey's band. It was Phil Moore, Executive Director in the UNIX Engineering team at Morgan Stanley.

"I work for the 38th largest company in the world", he began. "Morgan Stanley. We have a billion dollar IT budget. And we use a little of everything. Unfortunately. Excuse me, a LOT of everything. The trend I've seen in the last ten years...is the exponential growth in the variety and the depth and breadth of installation of open source software in our infrastructure...What I'm seeing is that in the infrastructure, the core infrastructure, open source is going to take over, leaps and bounds...I'm predicting, right now, that by two thousand-six or -seven, we're going to be a ninety percent Linux shop".

He spoke for several minutes, pacing in front of the stage, addressing both the audience and the panel. When he finished, there was applause.

There are three reasons, beyond the content of his talk, that Phil's speech was so compelling. First, he was a customer, rather than a vendor. It's customary at trade shows for vendors to fill session panels. As good as this panel was, nothing any panelist could say carried the authority that comes only from real customers. Second, Phil clarified market roles by making it obvious that customers are in charge of adoption. Not vendors. Third, he testified to the enormous success of SCO's FUD campaign by being courageous enough to stand up and speak out about it.

At one point in his soliloquy, Phil said, "We're still mostly a Solaris shop, but we are rapidly moving to Linux, though I'm not supposed to talk about that, for fear of being sued by SCO." Then he turned to Matt Asay and said, "Which is the reason why I couldn't go to your conference, the OSBC. I wasn't allowed to go." That filled a blank for me, because Phil was slated to be on my DIY-IT panel at OSBC, and couldn't make it. Now I knew why. That brought the number of AWOL panelists to two (out of the original four). The other panelist came to the conference, but was told at the last minute by his employer that he couldn't speak, and ended up sitting in the audience. Significantly, the two absentees were from large companies with buildings full of lawyers. To his (and his employer's) credit, R0ml Lefkowitz of AT&T Wireless did make the panel (as well as a speech of his own the same day at the conference).

But at OSCon Phil got to speak, and the message he carried was one I've been hearing privately as well from many other IT professionals: Linux is rapidly becoming default infrastructure, and open source the preferred code condition for all infrastructure.

Not that they're abandoning Microsoft. Far from it. But Microsoft's primary goods -- desktop operating systems and applications -- are becoming niched to the verge of quarantine. Phil made this clear when he turned to Jason Matusow of Microsoft and said "You can have the desktop. It's a pain in the ass. I don't want it. I just want the (core) where all the money's made."

Later he added, "I will bet my career that Microsoft is going to get wiped out on the desktop in the next ten years. Not in this country." Turning again to Jason, he said, "You're going to own it here because America loves you guys. You're set, for at least ten years." Turning back to the audience, he continued, "Look overseas at what's happening (with Linux). It doesn't matter what distribution. Because (Linux is) economical for people in foreign countries. It lets them invest in their own local software companies without putting money into these guys' pockets (indicates Microsoft), or some other foreign corporation that doesn't have a vested interest in your own economy and your own culture. That's going to be the number one reason why open source ends up taking over the planet."

As for other commercial vendors serving the IT space, he said, "I think you'll see proprietary companies shifted out to the leaf nodes, coming up with special purpose applications that are difficult to do on a large scale."

But in his current role an enterprise IT architect, Phil Moore still supports Windows desktops in the midst of a growing infrastructure comprised of Linux and other open source building materials -- and expects to maintain that relationship for the forseeable future.

While Phil and the others were talking, I realized that open source and the traditional commercial software industry are only at crossed purposes where they compete outright. But when Linux and open source products serve as infrastructural support, Windows OSes and apps get supported along with everything else.

In conversations that followed, out in the halls at OSCon and in subsequent meetings at OSCon and Linux World Expo (which followed the next week), I began to visualize the subject, starting with the traditional industrial market model:

This model was best described by John Perry Barlow in his 1995 essay "Death From Above", which argued against the asymmetrical bandwidth delivery plants that the cable and phone companies were then just beginning to build out. Here's how it begins:

Over the last 30 years, the American CEO Corps has included an astonishingly large percentage of men who piloted bombers during World War II. For some reason not so difficult to guess, dropping explosives on people from commanding heights served as a great place to develop a world view compatible with the management of a large post-war corporation.

It was an experience particularly suited to the style of broadcast media. Aerial bombardment is clearly a one-to-many, half-duplex medium, offering the bomber a commanding position over his "market" and terrific economies of scale.

Now, most of these jut-jawed former flyboys are out to pasture on various golf courses, but just as they left their legacy in the still thriving Cold War machinery of the National Security State, so their cultural perspective remains deeply, perhaps permanently, embedded in the corporate institutions they led for so long, whether in media or manufacturing. America remains a place where companies produce and consumers consume in an economic relationship which is still as asymmetrical as that of bomber to bombee.

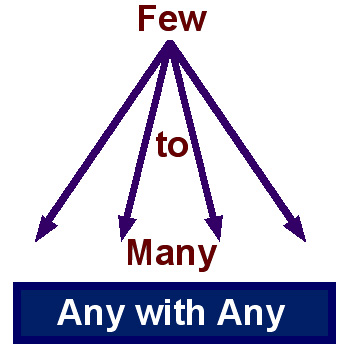

This industrial tradition has a number of ideals. The most obvious one is to sell unique and proprietary products to the largest number of people. Less obvious, but no less important, is to create and sustain market categories populated with intermediaries, and to hold as many dependents as possible -- from distributors and OEMs on down to customers -- captive on the manufacturer's platform.

The open source and free software movements are driven by ideals that are roughly orthogonal to the few-to-many model. To describe those ideals, it helps to start with the NEA qualities of open source products:

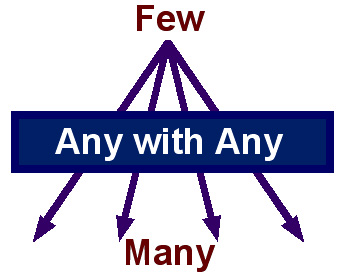

Manifest in the open communications infrastructure we call the Internet, this architecture is

It's tempting to call this "Peer to Peer"; but "to" is not the operative preposition here. Hacking may involve the transport of packets, but the collaborative activities involved are "with", not "to".

Juxtapose Any with Any on Few to Many, and you can see the cross-purposed result:

It's easy to see how this presents a problem -- not just for software manufacturing giants like Microsoft, but for Few to Many empires like the entertainment industry and consumer electronics. "Protecting" Few to Many from Any with Any became a cause for the whole entertainment industry. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act, lobbied through Congress in 1998, is landmark achievement in paranoia.

Yet now large customers like Morgan Stanley show us we misconceive the market when we only see conflict between open source and commercial software business imperatives. They make this clear when they put Any with Any in a supportive position beneath Few to Many:

Here the role of Any with Any is...

Of course, Few to Many is not the only market relationship supported by Any-with-Any infrastructure. By its relationship-agnostic nature, Any with Any can include and support Peer to Peer, Many to Many, Business to Business -- or any other pair of nouns flanking a presposition.

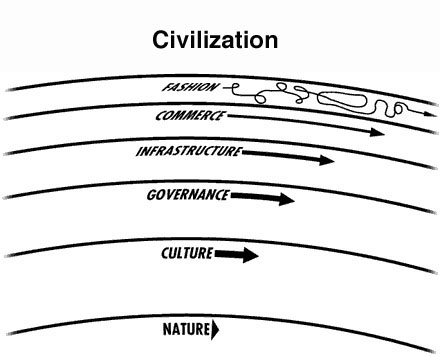

So, if Linux is infrastructure, where does infrastructure fit? This question matters, because it provides the context inside which paranoid Few to Many forces attempt to control infrastructure, and prevent Any with Any from working.

That context is best described in the "layers of time" diagram from the Long Now foundation that we first visited in May, 2002 <http://linuxjournal.com/article.php?sid=6074>:

This is a model of basic dependencies, as well as a way to sort out differences in rates of change. Each higher level depends on the one below it. That's how the Few to Many system, which operates at the Commerce level, depends on Infrastructure. It's also why commercial interests often work to control infrastructure one layer below, at the Governance level, often with great success. In fact, regulatory systems around the world have served commercial interests for centuries.

Open source infrastructure, however, was established at fashion-level speeds -- faster than industrial establishments could react in mast cases. Given the amorphous and ungovernable nature of the Net, regulating it presented a severe challenge. Plus, it brought too many benefits. Today it's a risk for companies not to take advantage of Any with Any infrastructure.

The single unqualified lobbying success against Any with Any was the DMCA -- a big, bad, dumb piece of legislation that needs to be repealed. But meanwhile there is still plenty of badness reposing in old copyright and patent law. Without that badness SCO's FUD campaign would not have been so successful. And that success is much more widespread than it appears, precisely because it's working. With the rare exception of guys like Phil Moore, IT workers at big companies aren't telling Linux success stories.

I've avoided writing about SCO ever since it made news by suing IBM early last year. First, I believed SCO had no case. (To borrow from the vernacular, they were "a flea floating down the river on its back with a hard-on, yelling 'raise the bridge!'") Second, given this column's three-month lead time, writing about the subject seemed pointless. But paranoia about discussing Linux and open source has become a prevailing condition inside large companies. Legal departments began putting IT workers (and everybody else) under gag orders as soon as SCO began suing large customers like Daimler-Chrysler. This has caused a news hole of massive dimensions, even though it's not especially visible at vendor-centric conferences or in vendor-driven publications.

So, while everybody continues to handicap the futures market in Linux desktops, the real challenge is just talking about how successful Linux really is, in the enormous (and far more important) market for enterprise infrastructure.