December 17, 1999

My Uncle Chris died yesterday morning, just before dawn, surrounded by his wife and five sons, at his home in Graham, North Carolina. In addition to his immediate family, he is survived by thirteen grandchildren, dozens of nieces and nephews, thousands of former patients, the church and town he helped build, and the Wake Forest Demon Deacons, all of which will be diminished by his passing.

Uncle Chris with his mother, "Granny" Crissman

He was eighty-five years old. For forty-five of those years, he was Graham's family doctor. If Andy Griffith had played a doctor instead of a sheriff, his model would have been Clinton S. Crissman, MD. Uncle Chris grew up in the same part of North Carolina as Sheriff Andy Taylor, and Graham was a real-life Mayberry: one of those little Southern county seats with the courthouse in the square and the Confederate soldier statue facing north up Main Street.

Although Graham was no less segregated than most southern towns in the Forties and Fifties, Uncle Chris was always everybody's doctor. Over the course of his career he delivered more than three thousand babies, including at least one Miss North Carolina. I doubt that other human being has ever done more good, personally, for the people of Alamance County than Doctor Crissman.

Uncle Chris was a Good Man in the purest meaning of that expression. He was more than a doctor. He was a healer. When he put his arm around you, looked you square in the eye and said "I believe you're gonna be all right," you were on the best drug the good Lord ever made.

Case in point. Back around the turn of the Eighties, when I was still a young man, I was seized by chest pains at work. I went to my local doctor, who didn't like my EKG and promptly put me under Intensive Care at Durham County General Hospital. A week later we found that it was only pleurisy, but for a while there it was scary.Doctor Crissman with grandsons Steven and Andrew

While we were all wondering what this was about, nobody did more to calm me down than Uncle Chris. He drove down from his office, forty miles away, put his strong hands on my legs, looked me in the face and said, with grave authority, "Now David, your job is to hold down the bed. You just do what these nurses tell you to do and you'll be all right."

In those days I knew lots of doctors, including several who worked in the local health care system, and I talked Science with every one of them. But none did more to heal me than Uncle Chris, with his strong hands and plain words. If I tried to talk Science with him, he'd just smile and joke back. saying, "Well, David, I think you know more about that than I do."

Of course, I didn't know squat. And most of my doctor friends didn't know a zillionth of what Uncle Chris knew in his bones about what makes people sick and well.

My cousin Mark, who took over his father's practice a few years ago, marvels at how much medicine his old man practiced without the aid of modern technology — and how successful he was at it. I believe it's because Uncle Chris was a natural. Love is always the best medicine; and God never made a doctor who was better at delivering that medicine. Especially to kids.

Whether he was giving us polio shots, carving up a watermelon or hauling us around to church, school or countless athletic events, he was always warm, funny, generous and

affectionate. But those are all just adjectives: brochure words. Where they all came together was with those big hands of his. "Hands are the heart's landscape," says Pope John Paul II. They are also the best metaphor or for care (from the Allstate slogan to Christ's last words on the cross). For countless children, patients and friends, those hands were the places to be.Uncle Chris with granddaughters Laura and Julie

When I look at these pictures of Uncle Chris, which I harvested from old family photo albums, the hands strike me again as perfect instruments of love and care. It's easy to see their effect on his grandchildren — the same effect their parents, aunts and uncles experienced a generation earlier.

Even as an adult, I loved the way Uncle Chris would hold people while he talked with them — or even while he was talking with someone else. I think I'll miss that even more than talking with him about basketball, especially his beloved Deacons. If I didn't bring them up right away, he'd say, "David, you haven't asked me about my Deacons yet."

Uncle Chris went to college at Wake Forest University, as did sons Paul and Charles. He was a loyal member of the Deacon's Club, and often traveled with the team. Once in a shopping center I ran into Rod Griffin, one of Wake Forest's basketball greats. I asked him if he knew Doctor Crissman and he said "of course," making it clear that the good doctor was among the team's favorite Deacon Club members.

Uncle Chris' affections and appreciations were not limited to the Deacons alone, however. Next to the Deacons he loved to follow all of ACC basketball, and beyond that the rest of the college game. I remember how he was moved to tears when David Thompson, the N.C. State star, was injured in an especially brutal accident under the basket. "I love that boy," he said to me. "I just hate to see that happen." But the truth was that Uncle Chris loved just about everybody, as far as I could tell.

Even though our family lived 500 miles away, in New Jersey, we were always in the Crissman orbit. At least once a year — usually on Easter, at the height of North Carolina's dogwood season — we would drive down to visit with the Crissmans on their farm-size property (bought in the early Fifties from next-door neighbor Tom Zachary, the great baseball player best known for pitching Babe Ruth's 60th home run). Uncle Chris and Aunt Doris (my mother's sister) had five boys. The first two, Paul and Erick, were the same ages as me and my sister Janet. The other three, Charles, Mark and Kelly, were no less fun.

The Crissmans had ponies, dogs, cats, and other animals that roamed the acres of grass and trees. With a spread that big, everybody worked like farmhands when they weren't having fun. For kids it was paradise. And there was never any doubt about who made it that way.Uncle Chris surrounded by sons Erick, Kelly, and Charles; granddaughters Karen, Emily, Julie, Melanie and Kate; daughters-in-law Linda and Patt; and grandson Steven

In my mind I can still see the original property — twenty-six acres of rolling pasture, populated by a single tree. Near that tree Uncle Chris built a large ranch house that was ideal for a family with four (soon five) active boys. The pool came soon after the house, then the barn, the gardens, the greenhouse, the bamboo grove and then the hundreds of new trees. Today those trees, mostly hardwoods, are huge. They also comprise some of the prettiest woods in the whole state: silent testimony to the nurture in their author's nature.

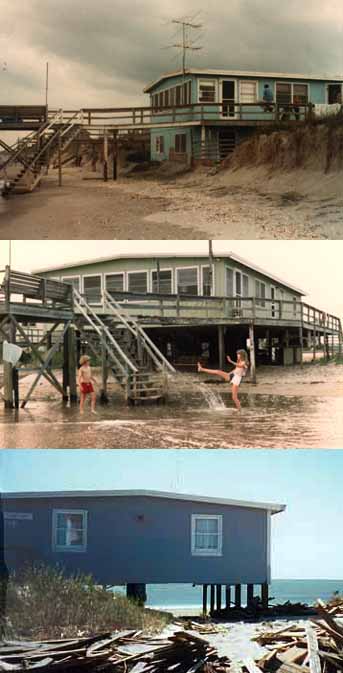

The Wheel House in 1974, 1980 (after Hurricanes David and Fredrick) and 1999 (after Hurricanes Dennis and Floyd)

Like those trees, all of Uncle Chris's sons, nieces and nephews are in now their forties and fifties (his first son Paul and I are the oldest, at 52). When my wife Joyce first met the whole family, she said "those are all such good men." It's easy to see why.

In the Seventies, when Uncle Chris and his generation were starting to retire, his wife Doris's two sisters, Eleanor (my mom) and Margaret both moved to Graham (Mom with my father from New Jersey and Aunt Maggie from California). So did I, with my wife and two kids. The gravitational pull was that strong.

March, 1974 was a rough month for my own little family. Colette was three and Peter had just turned one. My radio career in New Jersey had fizzled, my credit was shot, my car barely ran and my wife was sick. We needed a place to stay and Uncle Chris provided one. It was a giant old house on Main Street in Graham that had gone unoccupied for so long that the mailman refused to come to the door because the place was clearly "hainted." Uncle Chris let the four of us live there free of charge until I could get a steady job and we moved to Chapel Hill. He never asked for, or expected, a dime.

He was also generous with another amazing piece of real estate: The Wheel House — the Crissman's family retreat at Long Beach, North Carolina. This simple box has always been closer to the water than anything else around, always expected to be trashed by a hurricane, and always a survivor after hurricanes pass through. I'm not sure if it signifies anything, but it seems worth noting all the same.

There are so many other things I could say about Uncle Chris. How he was the best man at my second wedding. How he survived the tragic premature death of his beloved Doris and later married a dear friend, Bernice, who in the difficult final months of his life returned the good care he had given so many others over the years. How much Mom, who now calls herself "the last twig on the tree" of her generation, will miss his visits to her house. How he gave so much to the Methodist Church he helped build, to the schools, to the community. How hard it is to imagine a world without him.

Of course he's still here. The love he gave so abundantly continues to grow and spread;' because that's what love does. And that's what he knew perhaps better than anybody else around.

— David "Doc" Searls

Emerald Hills, California